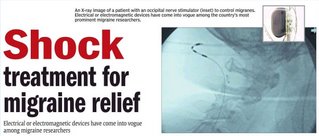

After shock - Shock treatment for migraine relief

Electrical or electromagnetic devices have come into vogue among migraine researchers

Electrical or electromagnetic devices have come into vogue among migraine researchers Amanda Schaffer

In ancient Rome, patients with unbearable head pain were sometimes treated with jolts from the electricity-producing black torpedo fish, or electric ray.

Electric fish have long disappeared from the medical armamentarium. But recently, electrical or electromagnetic devices that hark back to the head-zapping

torpedo fish have come into vogue among the country’s prominent migraine researchers.

Two different kinds of stimulatory devices are now in large-scale clinical trials for possible use in patients with the most severe migraine cases. The the

two kinds of stimulatory approaches are occipital nerve stimulation, or ONS, and transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS.

In occipital nerve stimulation, a pacemakerlike device is connected to electrodes placed at the back of the head just under the skin. Electrical current is

delivered through these electrodes, with the goal of inhibiting or preventing migraine pain. In transcranial magnetic stimulation, a magnetic device is

pressed to the back of the head, and brief pulses are delivered, altering electrical activity inside the brain in hopes of halting the migraine before it

progresses. This approach is being studied only for patients whose migraines begin with an aura, or premonitory phase, that is typically characterized by

flashing lights or other visual disturbances.

Experts say approaches like these represent a powerful new trend in migraine research. Dr Joel R Saper, director of the neurological institute, said in the

treatment, electrodes are positioned to stimulate the greater occipital nerve, which runs along the back of the head on either side. The occipital nerve

converges in the upper or cervical spinal cord with the trigeminal system, which includes neurons and neural pathways responsible for conveying much of the

throbbing pain associated with migraine, he said. Saper says it is not clear precisely how occipital nerve stimulation works. But one possibility is that it

effectively inhibits activity in the trigeminal system, thereby dampening the patient’s pain.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation, the other type of stimulation being tested, does not require a surgical procedure. Rather, it uses magnetic pulses,

delivered through the skin, to induce electrical changes in a particular brain area.

Dr Yousef M Mohammad, a neurologist at Ohio State University Medical Center, said the idea of us ing electrical or electromagnetic stimulation to treat

migraines resulted partly from a shift in how neurologists understood the disorder.

Modern medicine has viewed migraines primarily as a vascular problem. Blood vessels in the brain constricted, then subsequently dilated, irritating the nerve

endings around them and causing pulsating pain.

More recently, however, scientists have come to view these vascular changes as secondary to underlying neural events. For some patients who experience an

aura, a wave of electrical excitation appears to spread through an area of the brain called the occipital cortex.

Because this area governs vision, patients may see flashing lights, dancing bright spots or wavy lines, or they may experience a blind spot in their vision.

If the excitation spreads to other areas, other neurological symptoms — like numbness, tingling or difficulty speaking — may occur.

Intense excitation is soon followed by exhaustion or depression of the affected brain cells, Mohammad said. The end result of this process, known technically

as “cortical-spreading depression,” is irritation of trigeminal nerve fibers — and a throbbing, pounding headache.

The goal of transcranial magnetic stimulation is to interfere with the initial wave of excitation, thereby preventing the migraine from proceeding to the

headache phase.

In ancient Rome, patients with unbearable head pain were sometimes treated with jolts from the electricity-producing black torpedo fish, or electric ray.

Electric fish have long disappeared from the medical armamentarium. But recently, electrical or electromagnetic devices that hark back to the head-zapping

torpedo fish have come into vogue among the country’s prominent migraine researchers.

Two different kinds of stimulatory devices are now in large-scale clinical trials for possible use in patients with the most severe migraine cases. The the

two kinds of stimulatory approaches are occipital nerve stimulation, or ONS, and transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS.

In occipital nerve stimulation, a pacemakerlike device is connected to electrodes placed at the back of the head just under the skin. Electrical current is

delivered through these electrodes, with the goal of inhibiting or preventing migraine pain. In transcranial magnetic stimulation, a magnetic device is

pressed to the back of the head, and brief pulses are delivered, altering electrical activity inside the brain in hopes of halting the migraine before it

progresses. This approach is being studied only for patients whose migraines begin with an aura, or premonitory phase, that is typically characterized by

flashing lights or other visual disturbances.

Experts say approaches like these represent a powerful new trend in migraine research. Dr Joel R Saper, director of the neurological institute, said in the

treatment, electrodes are positioned to stimulate the greater occipital nerve, which runs along the back of the head on either side. The occipital nerve

converges in the upper or cervical spinal cord with the trigeminal system, which includes neurons and neural pathways responsible for conveying much of the

throbbing pain associated with migraine, he said. Saper says it is not clear precisely how occipital nerve stimulation works. But one possibility is that it

effectively inhibits activity in the trigeminal system, thereby dampening the patient’s pain.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation, the other type of stimulation being tested, does not require a surgical procedure. Rather, it uses magnetic pulses,

delivered through the skin, to induce electrical changes in a particular brain area.

Dr Yousef M Mohammad, a neurologist at Ohio State University Medical Center, said the idea of us ing electrical or electromagnetic stimulation to treat

migraines resulted partly from a shift in how neurologists understood the disorder.

Modern medicine has viewed migraines primarily as a vascular problem. Blood vessels in the brain constricted, then subsequently dilated, irritating the nerve

endings around them and causing pulsating pain.

More recently, however, scientists have come to view these vascular changes as secondary to underlying neural events. For some patients who experience an

aura, a wave of electrical excitation appears to spread through an area of the brain called the occipital cortex.

Because this area governs vision, patients may see flashing lights, dancing bright spots or wavy lines, or they may experience a blind spot in their vision.

If the excitation spreads to other areas, other neurological symptoms — like numbness, tingling or difficulty speaking — may occur.

Intense excitation is soon followed by exhaustion or depression of the affected brain cells, Mohammad said. The end result of this process, known technically

as “cortical-spreading depression,” is irritation of trigeminal nerve fibers — and a throbbing, pounding headache.

The goal of transcranial magnetic stimulation is to interfere with the initial wave of excitation, thereby preventing the migraine from proceeding to the

headache phase.

Comments