james Bond - Her Majesty’s Sacred Service

Simon Winder

Simon WinderLondon:

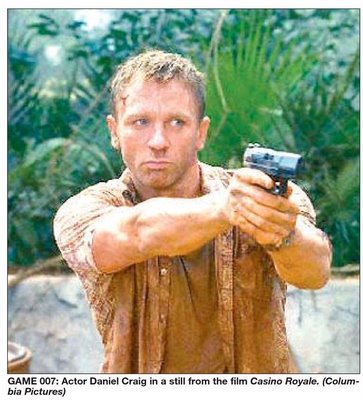

Half a cen tury after his invention, having now outlived his creator by more than 40 years, James Bond has taken on an almost religious role in our lives, miraculously reincarnating and retooling. His arrival in multiplexes in his fresh, blond avatar, Daniel Craig, adds to this mystic atmosphere.

The film, Casino Royale, is a remake based on the first of Ian Fleming’s Bond books: an attempt to return the character to his roots, a fresh beginning after the increasingly witless Pierce Brosnan years. In astrological terms, this is the equivalent of several planets or suns or whatever being perfectly aligned.

Will Bond’s latest rebirth usher in some new era in our history? The comparison is far from facetious. Like all cults, the Bond sect has gained strength through a constant rain of setbacks and humiliations. The wild success of the books and the initial 1960s films created the range of texts against which all later experience has been judged. Ian Fleming and Sean Connery between them established something glamorous, plausible and new. Have their successors maintained or enhanced this faith? Certainly looking at such old Roger Moore movies as that 1979 piece of desperation Moonraker one would have to say no. A truly terrible attempt to make Bond relevant to the Star Wars generation by sending a visibly puffy and slow-moving Moore into space, this and other Bond films of the period (has anyone watched A View to a Kill lately?) now look like the dying embers of a once burning faith.

After Moore reached the point where he needed almost to be helped up from his chair, the succession was passed to the featureless Timothy Dalton, who made two unloved movies before the whole thing faltered and died in a welter of legal disputes. The six-year break that followed was a weary desert for millions of fans: a time of testing common to many creeds.

After Moore reached the point where he needed almost to be helped up from his chair, the succession was passed to the featureless Timothy Dalton, who made two unloved movies before the whole thing faltered and died in a welter of legal disputes. The six-year break that followed was a weary desert for millions of fans: a time of testing common to many creeds.This fervent belief in James Bond was rewarded by his re-emergence as Pierce Brosnan in 1995’s GoldenEye. I have always felt Brosnan was a false prophet — a figure more at home modelling chunky watches or conservative suits than fulfilling Bond’s homicidal and sexual core competencies. But the scale of his films’ success at last banished Connery’s ghost. His followers may have been misled, but there could be no arguing with the immense, fervid crowds Brosnan could draw. Now the process begins again. Visibly too old in Die Another Day, Brosnan was ruthlessly left out in the wilderness and the hunt began once more for the true incarna tion. Whether Daniel Craig proves to be the new Connery or just the new Dalton will soon emerge.

Casino Royale is a stripped-down, ascetic, close-to-scripture production (at least, relatively so). This has happened several times before in Bond’s life. At the point where the films become simply too bloated and depressing (You Only Live Twice, Moonraker) there has been a corrective process (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, For Your Eyes Only) of weaning Bond off his gadgets and massed, doomed phalanxes of jump-suited security guards, in favour of the small scale and mildly realistic. But the result has tended to be somewhat boring films. Still, the last of the Brosnan epics, Die Another Day, with its invisible car, ice palace, death ray satellite and useless computer-generated images, certainly cried out for some kind of Reformation. In the wake of such a welter of exploding vehicles, smirking and physically memorable henchman and flawed plots for global domination, over so many books and so many films, how has Bond maintained this appeal? Perhaps it is as simple as the original idea being a very good one: a secret agent for a nuclear age rooted in a global myth of Britishness.

Gunning people down while sipping fine old brandies, Bond has certainly created a comforting nostalgia for the British, an amusing sardonic role model for Americans and (as with the roots of so many faiths) he comfortably feeds into many countries’ pre-existing ideas: in this case, of British violence, faithlessness and snobbery. That over the decades fans have had necessarily to endure a vertiginous shape shifting element in the figure of Bond (now Scottish, now rather old, now Irish, now incredibly dull) makes him ever more powerful, beyond the vagaries of the merely human.

It could be, of course, that we are only in the very early stages of James Bond’s existence. He is not as old as Batman or Spiderman, but he is notionally supposed to be more realistic than either — although saving the world with the characteristics of a bat or spider is not on the face of it less plausible than saving the world as an erotomaniacal British toff.

It could be, of course, that we are only in the very early stages of James Bond’s existence. He is not as old as Batman or Spiderman, but he is notionally supposed to be more realistic than either — although saving the world with the characteristics of a bat or spider is not on the face of it less plausible than saving the world as an erotomaniacal British toff.(Simon Winder is the author of The Man Who Saved Britain: A Personal Journey Into the Disturbing World of James Bond.)

Comments